Common Operating Picture and Situational Awareness

This series of posts began with a simple question related to a one-story house with a walkout basement on Side Charlie, “how do I describe the number of stories and basement in my follow-up report”? The second post in the series, dug a bit deeper into the importance of variation in the number of stories on different sides of the building and some critical considerations related to basement fires.

This post will back up and examine the larger concepts of developing and maintaining a common operating picture and shared situational awareness. The concepts of a common operating picture and shared situational awareness are closely related and essential to safe and effective incident operations

Common Operating Picture

Originating from the military, the term common operating picture often refers to a dynamic, real-time visual representation of an operation, providing a shared understanding of what’s happening on the ground. A COP is continuously updated for the duration of an operation from data shared between integrated communication, information management, and intelligence and information sharing systems (Steen-Tveit & Munkvold, 2021 & DHS S&T, 2008).

It is easy to see how a COP could have a positive impact on large scale incident operations such as response to a natural disaster or large wildland fire, but how does this apply to rapidly changing, dynamic nature of structural firefighting operations that occur within a (relatively) short operational period?

Consider developing and maintaining a common operating picture on a micro level with three engines, ladder company, medic unit, and command officer responding to residential fire. Building a COP includes some or all the following:

- Dispatch information provided via the station alerting system and over the tapout talk group/frequency.

- Computer aided dispatch (CAD) incident information provided via mobile data computer (MDC).

- Maps and pre-plan data on the MDC or hard copy in the apparatus.

- Additional information provided by the dispatcher on the tactical talk group/frequency.

- Initial radio report provided by the initial incident commander (IC #1).

- Update report following 360-degree reconnaissance or information that reconnaissance was not completed (and why).

- Knowledge of the community (typical occupancies by location, age of buildings, typical layout and configuration, etc.). Important! This may or may not be consistent across all personnel responding to this incident (this requires ongoing training).

All responding companies have the same information and communications by the initial incident commander lay the foundation for understanding “what is happening on the ground”.

Use of one talk group/frequency for communications with and between all hazard zone resources helps maintain the COP. Standard communications including task, location, and objective (TLO) tactical orders, conditions, actions, and needs (CAN) reports, priority traffic, and status changes on a common frequency keeps resources operating in the hazard zone updated on incident conditions and tactical operations.

Situational Awareness

Firefighters often refer to situational awareness (SA) and, in many cases, the occurrence of maydays is attributed to a loss of SA. But what exactly is situational awareness?

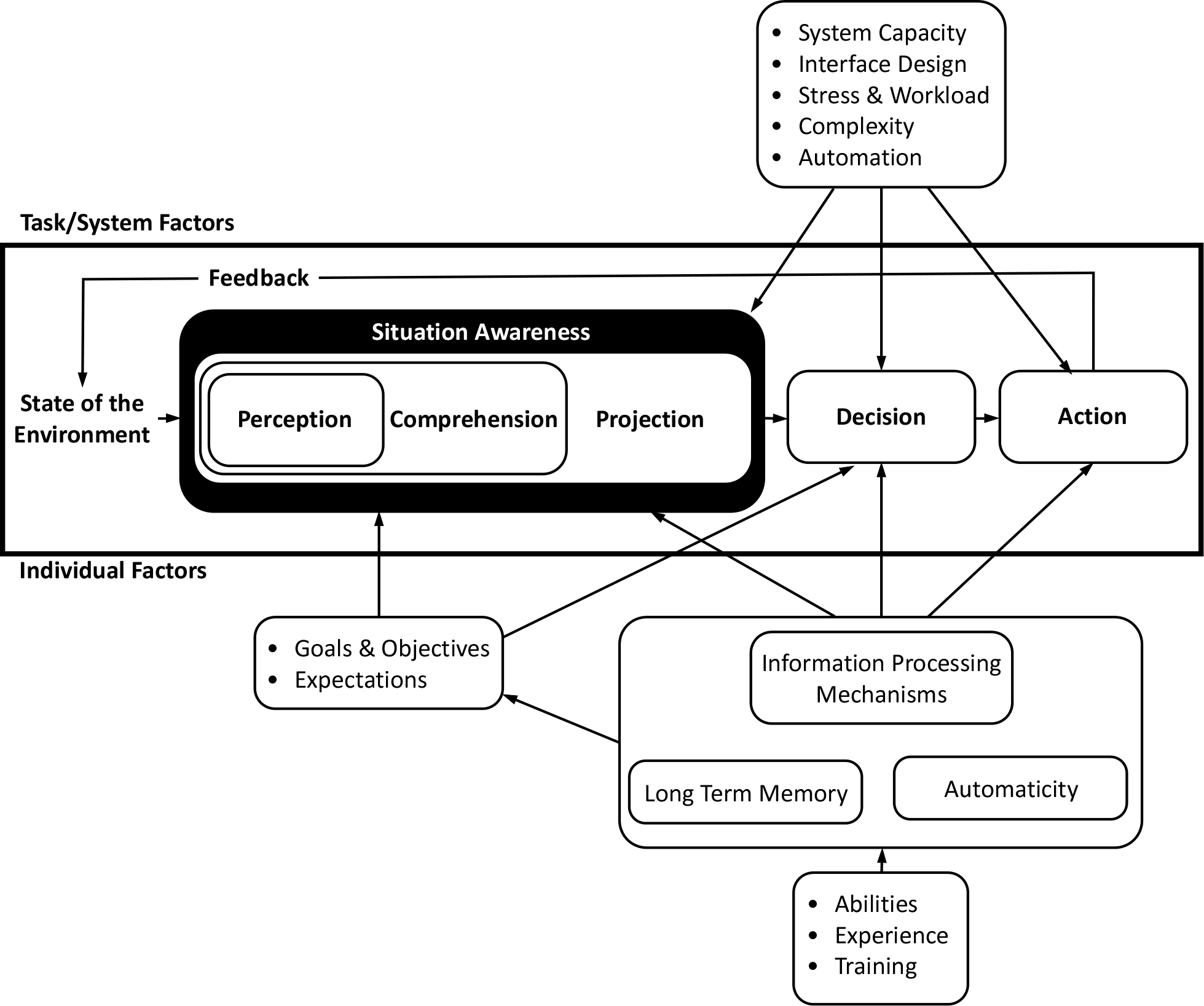

Endsley (1995) formally defines SA as “the perception of elements in the environment within a volume of time and space; comprehension of their meaning; and projection of their status in the near future” (p. 36) and more informally as “knowing what is going on“ (p. 36). Endsley s definition involves three hierarchical levels of SA comprising

- Perception: Detection, recognition, and identification of critical factors in the environment.

- Comprehension: Integrating the critical factors into a coherent understanding of the current situation, often involving mental models of the system.

- Projection: Interpretations and projection of future system states based on the prior levels and professional knowledge.

SA, decision making, and action in a dynamic context are influenced by a variety of task/system and individual factors.

Note: Adapted from Endsley, M. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems, Human Factors Journal, (37)1, 32-64.

Endsley’s definition and levels of SA are generic and apply in many different contexts. Think about how this applies in the context of response to the residential fire.

You have been dispatched to a residential fire at 06:00. You recognize the address is for a neighborhood of single family homes in a hilly area of the community. Most homes in this area were built in the 1980s and are occupied by working class families. Fire hydrants in this area have a flow rate of between 1000 gpm and 1500 gpm and are spaced approximately 500’ apart. While you are responding dispatch provides an update that they have received several calls reporting smoke from the house at the reported address.

What critical factors do you draw from this information? What is your understanding of the current situation, what do you anticipate finding on arrival? How do you think that conditions may change during your response?

You arrive at a small, one-story house with dark grey smoke from the eaves on Side Alpha with moderate velocity and dark gray to black smoke visible above the roofline, appearing to be coming from Side Charlie. The smoke that appears to be coming from Side Charlie is turbulent and rises quickly from the building. Exiting your apparatus to complete a 360, there are no occupants or bystanders outside the house, you observe that the large picture window on Side Alpha is dark, but window shades are visible in the smaller windows on the opposite end of Side Alpha.

What are the critical factors in this description of conditions? What is your understanding of the current situation? What do you think will happen in the next several minutes as you complete your reconnaissance, and your company goes to work based on your initial size-up and incident action plan?

You continue around Side Delta and find that the ground slopes down towards Side Charlie. There are no windows on Side Delta. On Side Charlie you find flames and black smoke from the sliding glass door in a walkout basement. The glass in the door is broken and there is a bi-directional flow, with smoke and flames exiting from the top half of the door. Smoke from the basement obscures the windows on Floor 1. You complete your 360 and find no windows on Side Bravo.

What are the critical factors in this description of conditions? What is your understanding of the current situation? What do you think will happen in the next several minutes as your company goes to work based on your revised incident action plan? How did your situational awareness change?

It is interesting to think about what influenced your situational awareness, what cues did you focus on, how did you recognize the current situation and project future conditions? It was likely based on your mental model of a residential basement fire in a small house with a walkout basement.

Shared Situational Awareness

“Shared situational awareness simply means two or more people have a commonly understood mental model – a mental image of what’s happening and what is going to happen in the future” (Gassaway, n.d).

In the context of operations at this residential fire, would the other members of your company have the same situational awareness as you do? Would the other companies? Would the command officer?

Each individual operating at this fire sees something different as conditions are dynamic and change quickly. Individual SA is influenced by the person’s experience and their own mental model of the situation. Within a company, shared SA is important and depends on effective communication between the company officer and members of the crew. Communicating “here’s what I think is going on and what I am concerned about” is an excellent starting point for developing shared company level SA.

All resources have similar information (except for community knowledge and prior experience) based on solid communications procedures. However, they will all perceive different conditions on arrival (better or worse than the first arriving company).

Gassaway states that in “an incident with one person defined as the commander who has watched the big picture incident (and all its changes from the start), in real-time, will likely have the best situational awareness”. However, unless the chief officer arrives first (filling the roles of IC #1 and #2), it is unlikely that anyone will have watched the big (strategic and tactical) picture throughout the entire incident. The first arriving company officer, who frequently serves as IC #1, has different situational awareness once they go to work at the task level and lose a strategic level view of incident operations. This is why an effective process of command transfer including a CAN report provided by IC #1 is so important.

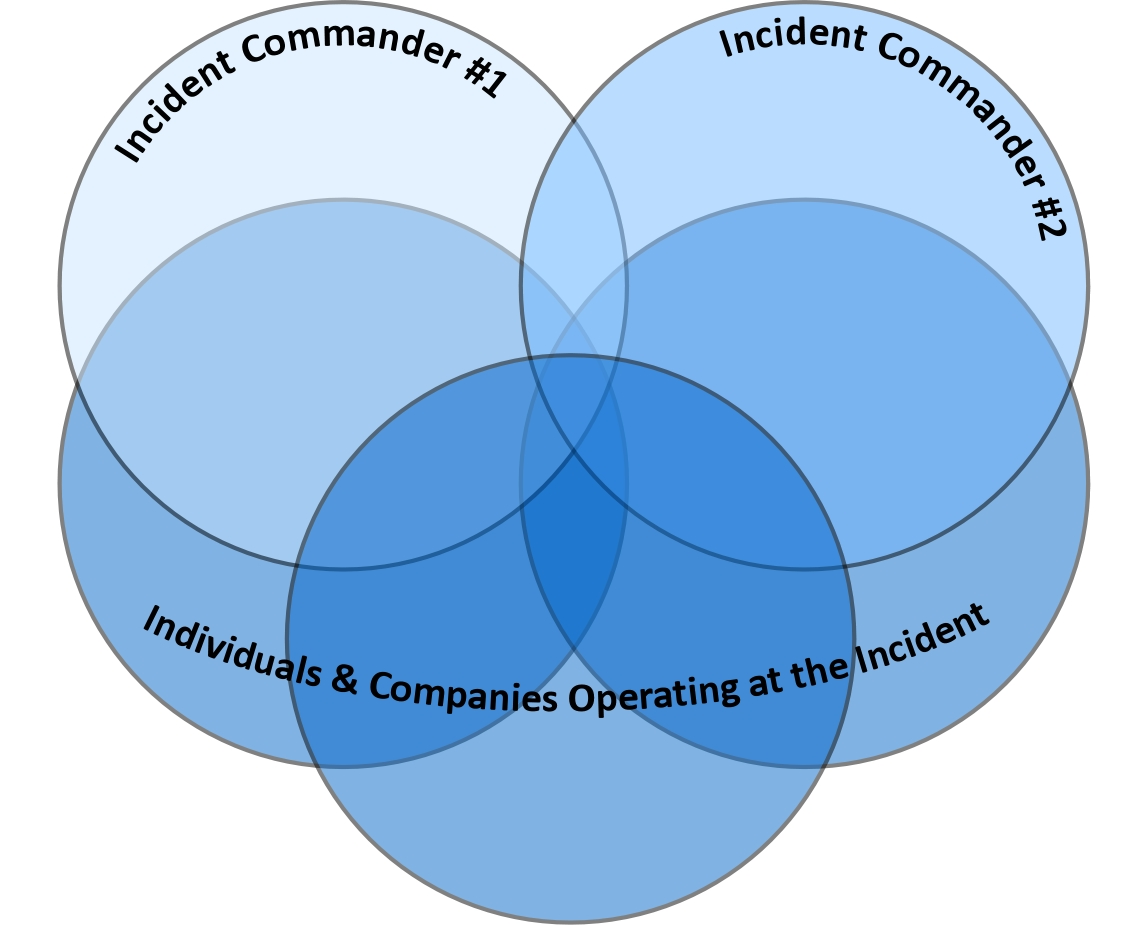

Endsley (1995) points out that each member of a team has a specific set of SA elements that they are concerned about based on their role and responsibility. IC #2 (the strategic IC), operating companies, and individual members of operating companies will all have different SA, but there should be areas of commonality.

Note: Adapted from Endsley, M. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems, Human Factors Journal, (37)1, 32-64.

As with building a common operating picture, effective communications are critical to developing and maintaining shared SA. While everyone will perceive the operating environment differently, within crew communications and CAN reports provide a level of commonality and shared understanding of “what is going on”.

Back to Basements and “Stories on Side Charlie”

We began this trilogy with a question about how to describe a house with a walkout basement on Side Charlie, but as we have progressed through these three posts, this was just the tip of the iceberg. Communications are an important component in ensuring that companies operating on the fireground and the IC have shared situational awareness and are on the same page strategically and tactically!

References

Steen-Tveit, K. & B. Munkvold (2021). From common operational picture to common situational understanding: An analysis based on practitioner perspectives, Safety Science, 142. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://bit.ly/4jit827.

Department of Homeland Security Office of Science and Technology (DHS S&T). (2008). Common operating picture for emergency responders. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://bit.ly/3Gw7p80.

Endsley, M. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems, Human Factors Journal, (37)1, 32-64.

Gassaway, R. (n.d.). Shared situational awareness [blog post]. Retrieved April 19, 2025, from https://bit.ly/431qKWD.