Smoke Explosion

One of the earliest descriptions of compartment fire explosions is the paper published by Steward in 1914. Steward used the term smoke explosion as a general term to distinguish between smoke gas explosions to dust explosions but did not differentiate between backdrafts and smoke explosions as fire behavior phenomenon.

“… ‘smoke explosions’ frequently occur in burning buildings and are commonly termed ‘back draughts’ or ‘hot air explosions. Fire in the lower portion of a building will often fill the entire structure with dense smoke before it is discovered issuing from crevices around the windows. Upon arrival of the firemen openings are made in the building which admit free air, and the mixture of air and heated gases of combustion are ignited with a flash on every floor, sometimes with sufficient force to blow out all the windows, doors of closed rooms where smoke has penetrated, ceilings under attics etc.” (Steward, 2014, p 427)

Let’s go back to the first post in this series and examine the differences between a backdraft and a smoke explosion:

Backdraft is a deflagration (explosion) resulting from increased ventilation of an enclosure containing a concentration of atmospheric oxygen that is too low to support significant flaming combustion and a high concentration of flammable products of combustion and unburned pyrolysis products (smoke) above their flammable range. A backdraft requires a high concentration of gas phase fuel, low oxygen concentration, and a change in ventilation.

Smoke explosion is a deflagration resulting from ignition of atmospheric oxygen, flammable unburned pyrolysis products and products of combustion (smoke) that are within their flammable range. A smoke explosion requires a mixture of fuel and atmospheric oxygen that are within their flammable range and ignition source (but no change in ventilation)

Researchers investigating the smoke explosion point to the fire and explosion at the Chatham Dockyards which resulted in the line of duty deaths of two firefighters and injured four others as an example of this phenomena (Sutherland, 1999; Chen, 2013; & Rasoulipour, 2022).

Wooley and Ames (1975) investigated this incident and the explosion risk presented by stored foam rubber. The Chatham Dockyards incident involved a fire in a store containing 178 foam rubber mattresses. On arrival, firefighters observed smoke from a partially open window. Entering the store, firefighters do not observe any flames, but encounter, cool, dense smoke forming a 0.5 m above the floor. Firefighters search for the seat of the fire without success and open several windows to ventilate the smoke. At this point an explosion occurred inside the building that was powerful enough to break windows but did not result in structural damage.

It is interesting to note that while multiple researchers identified the explosion that occurred at this incident as a smoke explosion, other researchers identified this incident as involving a backdraft (Fleischmann, 1994 & Chitty, 1994). This points to the significant challenge in identifying the smoke explosions that occur in the field and differentiating smoke explosions and backdrafts based on anecdotal evidence.

Multiple Scenarios

The most common scenario for a smoke explosion is accumulation of smoke in a compartment or void space adjacent to the fire compartment where the smoke mixes with air and develops a flammable mixture. The missing factor is a source of ignition. The flammable mixture of smoke and air may be ignited by extension of fire into the compartment or void space, or it may be unrelated to the fire. If there are no openings to relieve the pressure developed by the explosive combustion of the smoke and air, significant overpressure can result, potentially causing structural damage and collapse (Bengtsson, 2001).

Bengtsson (2001) provides an alternative scenario for a smoke explosion occurring in the fire compartment. This takes us back to the discussion of pulsating (vent limited) fire development as discussed in the third post in this series.

If normal building ventilation and leakage is not sufficient to maintain continued fire growth a ventilation-limited fire enters the decay stage. HRR and resulting temperatures will become lower, reducing pressure within the enclosure. As pressure drops, the exhaust of smoke through leakage points will become less pronounced and may cease entirely as the leakage points become air inlets. Intake of air will result in regrowth of the fire with increasing HRR and temperature, returning the leakage points to exhaust openings for smoke. The increased HRR results in increased oxygen consumption, resulting in the cycle repeating itself (Bengtsson, 2001 & Lambert & Baaij, 2011).

With pulsating fire development, sufficient temperature is maintained for ongoing pyrolysis of building contents and structural materials, increasing the concentration of flammable pyrolysis products in the smoke.

If the oxygen concentration remains low enough and the room continues to cool, the fire may self-extinguish. Given a high enough concentration of fuel and high enough temperature or a return to flaming combustion providing for piloted ignition, a backdraft could result. However, if the oxygen concentration rises sufficiently to bring the smoke and air mixture within the flammable range a glowing ember or flame from the initial fire may ignite the premixed smoke and air, resulting in a powerful smoke explosion (Bengtsson, 2001).

Bakka, Handal, and Log (2020) examined an incident occurring in a high voltage room at a methanol production facility where an explosion occurred as the result of overheating of combustibles which produced significant smoke (pyrolysis products) and formed a mixture within the flammable range and was subsequently ignited, resulting in an explosion. The authors termed this event as a quasi-smoke gas explosion as there was no initial fire, but at the end of the day it was the same type of phenomena as a smoke explosion.

Smoke Explosion Research

While there has been considerable research examining the backdraft phenomenon, there have been few studies examining smoke explosions. Smoke explosions have a brief mention in some fire dynamics texts (Drysdale, 2011 & Karlsson & Quintiere, 2000) and fire service training materials (IFSTA, 2024).

Wooley and Ames (1975) investigated the flammability of foam rubber and conducted qualitative experiments to determine if pyrolizates from foam rubber could create an explosive atmosphere within a small scale compartment. Experimental research focused specifically on the smoke explosion phenomena started at the University of Canterbury in 1996. Parkes (1996) investigated under-ventilated compartment fires as a precursor to smoke explosions. While Parkes’s small scale experiments using heptane as fuel did not produce any smoke explosions, his work provided detail on underventilated fires and characterized several ventilation parameters and their influence on combustion. The first substantive research on smoke explosions was conducted by Sutherland (1999) who conducted small scale experiments using medium density fiberboard (MDF) as fuel. Sutherland found a range of fuel and compartment ventilation conditions that lead to smoke explosions and that under the right conditions, a smoke explosion could occur in the fire compartment without a change in ventilation. Chen (2013) and Rasoulipour (2022) extended Sutherland’s initial research providing additional and more fine-grained detail.

Fleischmann, Madrzykowski, and Dow (2024) have continued investigation into overpressure events such as smoke explosions. Unlike prior research on smoke explosions by Sutherland (1999), Chen (2013), and Rasoulipour (2022), Fleischmann, Madrzykowski, and Dow conducted their experiments in a slightly larger scale compartment lined with plywood with a timber crib used as the initial fuel package.

Note: Adapted from Underwriters Laboratories Fire Safety Research Institute (UL FSRI). (2025). Backdraft and Smoke Explosions. https://bit.ly/4lRIP19.

Fleischmann, Madrzykowski, and Dow (2024) emphasize they used the term overpressure events rather than trying to fit specific occurrences of explosions during enclosure fires int the existing descriptions of backdraft and smoke explosion. “In the context of this paper, the events are simply referred to as overpressure events (OPE) described as the rapid expulsion of combustion products from a building followed immediately by flames that cannot be explained by the accidental release of flammable gases or the ignition of flammable liquids” (p. 1870).

As can be seen in the preceding table, most of the smoke explosion research has used medium density fiberboard (MDF) or wood. In contrast, smoke explosions, like backdrafts occurring in the built environment “occur in compartments filled with complex mixtures of partially burnt products of pyrolysis from solid fuels such as wood, plastics and foams. Such pyrolysis gases have a range of flammability limits and may only be flammable at elevated temperatures” (Wu, Santamaria, & Carvel, 202, p.2).

Concepts and Terminology

There are several concepts and a bit of terminology that are important in understanding the research into the phenomenon of smoke explosion. These include stoichiometric and equivalence ratios.

Stoichiometric Fuel/Air (or Oxygen) Radio

Combustion is a chemical reaction between fuel and oxygen releasing energy in the form of heat, and in the case of flaming combustion in the form of heat and light. The energy released by a specific mass of fuel when completely oxidized is its heat of combustion (ΔHc). When hydrocarbon fuels are burned in air, the products of complete combustion are carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). Nitrogen (N2) and other non-flammable constituents in air are not part of the chemical reaction but are thermal ballast that must be heated along with the fuel and air.

The stoichiometric fuel-air ration is the mixture of fuel and air necessary where there is just enough oxygen to fully oxidize the fuel. When hydrocarbons are burned under stoichiometric conditions, the mixture contains just enough oxygen (O2) to oxidize all the carbon (C) to carbon dioxide (CO2) and all the hydrogen (H2) to water (H2O).

Where there is more oxygen than needed for complete combustion, the fire may be described as fuel lean, fuel limited, or over ventilated. Under these conditions, additional oxygen will be mixed with the products of combustion. When there is insufficient oxygen for complete combustion, combustion can be described as fuel rich, ventilation limited, or underventilated. Products of incomplete combustion will include carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), more complex hydrocarbons, and soot. The exact stoichiometric mixture of fuel and air varies based on the chemical composition of the fuel.

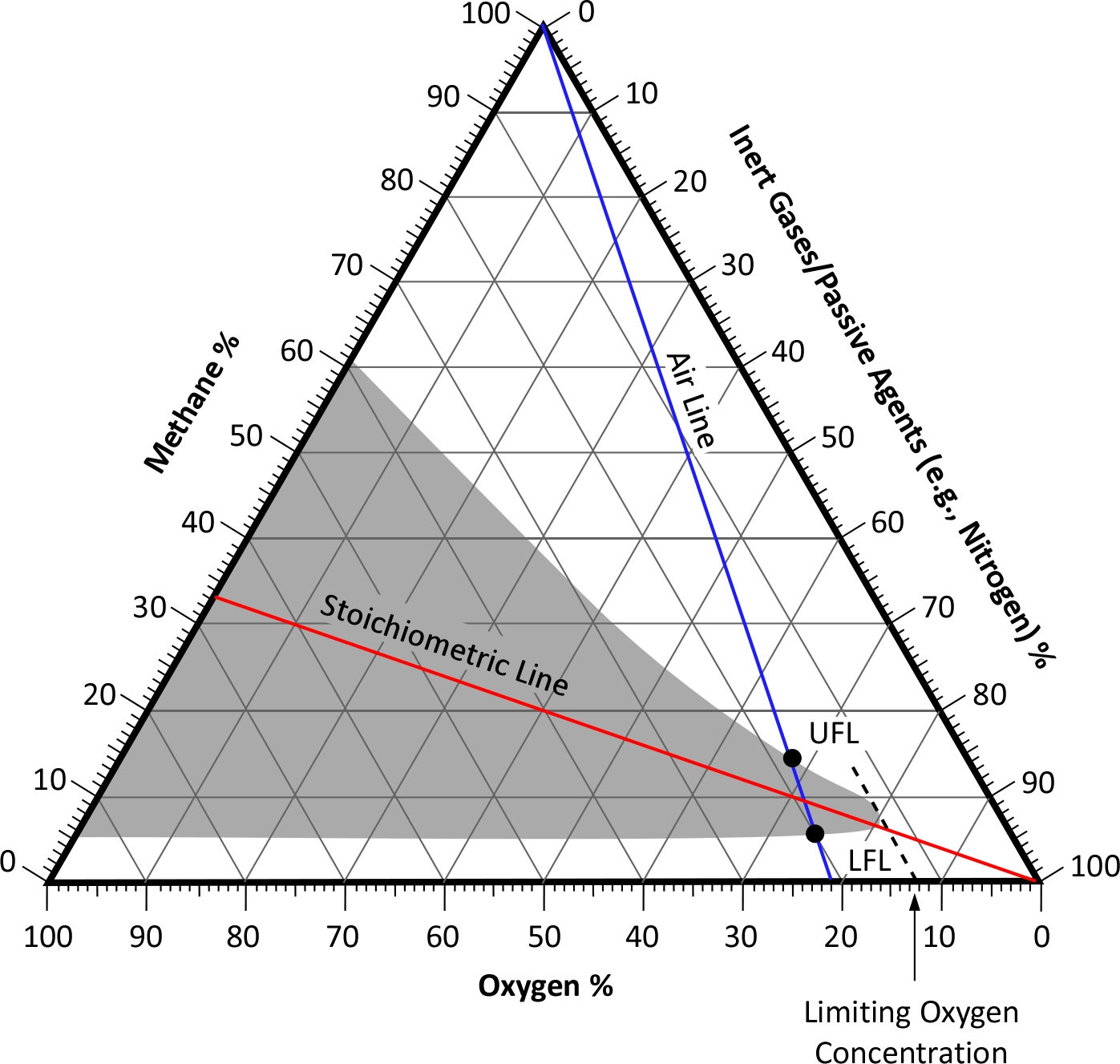

As discussed in a previous post, flammability diagrams can be used to present flammability limits for different mixtures of fuel, oxygen, and inert gases (such as nitrogen).

The blue air line identifies the ratio of oxygen and nitrogen in the normal atmosphere (21% O2, 79% N2). The grey area illustrates where the fuel/oxygen/nitrogen mixture is flammable. The grey area on the right side of the air line is when the oxygen concentration is lower than the ratio of oxygen in the air. When using the flammability diagram to understand the flammability of products of pyrolysis and combustion in a compartment fire, the grey area to the right of the air line is the area of interest.

The red, stoichiometric line illustrates mixtures of fuel and oxygen that will burn completely (stoichiometric combustion).

The dashed line identifies the minimum oxygen concentration required to form a flammable mixture, the limiting oxygen concentration (LOC). When a mixture of fuel, oxygen, and inert gases contain an oxygen concentration below this level, it is non-combustible.

Equivalence Ratio

Rasoulipour (2022) identifes that the equivalence ratio (ER) is a way to describe the ventilation conditions during a compartment fire. The equivalence ratio (Phi or Ø) Is a measure of the mixture of fuel and air as compared to the ideal, or stoichiometric, ratio. It indicates whether a combustion mixture is lean (excess air), rich (excess fuel), or stoichiometric (perfect balance). If Ø<1 there is more than enough oxygen available for complete combustion. If Ø>1 the mixture is fuel rich and there is insufficient oxygen available for complete combustion. When Ø=1, the mixture of fuel and oxygen is stoichiometric, containing the ideal mixture for complete combustion.

In compartment fires, the composition of products of pyrolysis and combustion are related to the equivalence ratio. When Ø≤1 combustion is likely to be more complete. When Ø>1, larger amounts of CO, total hydrocarbons (THC), and soot will be produced and if the fuel contains nitrogen, hydrogen cyanide (HCN) will also be a product of incomplete combustion.

Previous posts have discussed the concepts of fuel and ventilation limited burning regimes. In a compartment fire, the equivalence ratio distinguishes between fuel and ventilation limited conditions. If Ø≤1 there is adequate atmospheric oxygen, and the fire will be fuel limited. As oxygen is consumed by the fire the equivalence ratio will rise and when Ø>1 the fire will become ventilation limited (Gann & Bryner, 2008 & Pitts, 1994)

Factors Influencing Occurrence of a Smoke Explosion

Examining research conducted on the backdraft phenomena since Sutherland’s initial work in 1999, several common factors can be identified.

- The fire will burn in a ventilation limited regime for an extended period and transition to smoldering combustion prior to the occurrence of a smoke explosion. This transition to smoldering combustion lowers heat release rate, temperature, and consequently, the pressure within the compartment decreases.

- For smoke explosions occurring in the fire compartment, it is common for there to be a mass fraction of flammable produces of pyrolysis and combustion that is higher than the upper flammable limit, given the mass fraction of oxygen and the temperature within the enclosure prior to development of conditions required for a smoke explosion.

- There is no change in ventilation prior to the occurrence of a smoke explosion. As temperature and pressure within the compartment falls during smoldering combustion, inward leakage of air increases the mass fraction of oxygen.

- Ventilation resulting from normal building ventilation and leakage allows the mass fraction of oxygen to rebound, bringing the mixture of flammable products of pyrolysis and combustion and oxygen within the flammable range prior to occurrence of a smoke explosion.

- The mass fraction of flammable products of pyrolysis and combustion must be within the flammable range of the mixture, given the mass fraction of oxygen and temperature within the enclosure. However, a flammable mixture may exist without the occurrence of a smoke explosion.

- The equivalence ratio will generally be between 1.5 and 2.6 just prior to ignition resulting in a smoke explosion. An equivalence ratio of greater than 1.0 indicates that the fire is burning in a ventilation limited regime.

- The temperature within the enclosure immediately before the occurrence of a smoke explosion ranged between 330o C and 400o Rasoulipour (2022) concluded that smoke explosions may occur when the compartment temperature was above 330o C if a glowing ember or hot surface with sufficient energy to ignite the premixed gases was present.

- Smoke explosions require piloted ignition. The ignition source may be glowing embers or return of smoldering fuel to flaming combustion.

- Smoke explosions can result in significant overpressure, depending on the mixture of flammable products of pyrolysis and combustion and oxygen (the closer to a stoichiometric mixture, the more violent the explosion), and the degree of confinement provided by the enclosure (the greater the confinement, the greater the pressure that will result from a smoke explosion).

It is important to note that all the experimental research examining smoke explosions focused on the occurrence of smoke explosions within the fire compartment. No research has yet been conducted on the reportedly more common occurrence of smoke explosions remote from the fire area or in adjacent compartments or void spaces. Investigation of smoke explosions outside the fire compartment are likely to add to an understanding of this phenomenon and the factors influencing the occurrence of smoke explosions.

Burning Regime

Smoke explosions can occur when a fire is in the ventilation limited burning regime. Rasoulipour (2022) divides the ventilation limited burning regime on a qualitative basis into “underventilated” and “severely underventilated” conditions. Underventilated conditions are described as continuation of flaming combustion after the fire becomes ventilation limited. Severely underventilated conditions are described as the cessation of flaming combustion and transition to smoldering combustion.

Rasoulipour also examined the impact of “porosity” on combustion of a fuel package in an enclosure and its impact on potential for a smoke explosion.

Thomas and Nilsson have identified a third regime of burning that must be considered in which the crib structure controls the burning rate. The third regime, known as porosity-controlled regime, is when crib [fuel package] density over its volume is relatively high, and the crib itself could be viewed as an enclosure within the compartment (Rasoulipour, 2022, p. 16).

Porosity-limited burning refers to a regime where the fuel’s internal geometry and airflow limit the combustion rate. This phenomenon has been studied extensively with wood crib fuel packages. When individual sticks of wood forming a crib are closely spaced, the burning rate is limited by the amount of oxygen that can reach the inner surfaces of the crib.

Note: Adapted from McAllister, S., Grumstrup, T. (2023). Burning rate of wood cribs with controlled airflow. Fire Technology, 59, 3473–3492. https://bit.ly/4evzlWQ.

Porosity and ventilation limitations can coexist. A dense fuel in a very tight compartment might burn extremely slowly, governed by the most restrictive of the two limits. In this case the fire may initially be limited by porosity and then become ventilation limited once the overall oxygen concentration in the compartment is sufficiently reduced.

Rasoulipour’s (2022) research using medium-density fiberboard (MDF) cribs showed that both porosity-controlled cribs and surface-controlled (high-porosity) cribs can produce rich smoke and lead to smoke explosion/backdraft conditions when the compartment is under-ventilated While the burning rate of a dense crib is lower, it still produces flammable pyrolizates if oxygen is insufficient, just as a more open fuel would.

Consistent with a ventilation limited burning regime, Rasoulipour (2022) found that the equivalence ratio (Ø) was between 1.5 to 2.0 before the occurrence of smoke explosions. However, it was also necessary for the fire to transition to an underventilated condition (smoldering combustion) for normal ventilation to allow the oxygen concentration to increase and bring the products of pyrolysis and combustion into the flammable range.

Rasoulipour (2022) made several observations related to burning regime, underventilated and severely underventilated conditions.

- When flaming combustion transitions to smoldering combustion it can lead to conditions resulting in a smoke explosion.

- The experiments resulting in a smoke explosion generally occurred during smoldering combustion in a boundary region between flaming and smoldering combustion.

- Fire gas ignitions without overpressure may occur during flaming combustion when near the boundary region between flaming and smoldering combustion.

Smoldering Combustion

Sutherland (1999), Chen (2013), and Rasoulipour (2022) all identified smoldering combustion as a precursor to developing the requisite conditions for the occurrence of a smoke explosion.

“Only porous materials which form a solid carbonaceous char when heated can undergo self-sustained smouldering combustion” (Drysdale, 2011, p. 275). The term porosity can be a bit confusing as it may refer to the fuel package as previously discussed, or it may refer to the nature of the fuel itself. In the context of smoldering, porous fuels include paper, cellulosic fabrics, wood, latex rubber, and some thermosetting plastics. “Volatile pyrolizates resulting from smoldering combustion are a complex mixture of products including high boiling point liquids and tars which condense to form an aerosol, quite different from smoke produced in flaming combustion (Drysdale, 2011, p. 276).

Concentration of Gas Phase Fuel

For a smoke explosion to occur the mixture of unburned fuel and oxygen must be within the flammable range. When a compartment fire transitions from a fuel limited to a ventilation limited burning regime two things are happening simultaneously. The oxygen concentration decreases and the concentration of unburned fuel, carbon monoxide (CO) and total hydrocarbons (THC) increases. If the oxygen concentration decreases to below the limiting oxygen concentration before the concentration of unburned fuel reaches the lower flammable limit, a smoke explosion will not occur unless the fire becomes severely underventilated and the fire begins to smolder, reducing oxygen demand and allowing existing ventilation to increase the oxygen concentration, bringing the mixture into the flammable range.

The following flammability diagram for the pyrolysis products of medium density fiberboard (MDF) illustrates how the unburned fuel and oxygen concentration varied prior to occurrence of a smoke explosion in two of the experiments conducted by Rasoulipour (2022).

Note: Adapted from Rasoulipour, S. (2022). Experimental investigation of the smoke explosion phenomenon. https://bit.ly/43XccaI

Steady State Ventilation

A key difference between backdraft and smoke explosion is that a backdraft is initiated by a change in ventilation while a smoke explosion does not involve a change in ventilation. In a smoke explosion, ventilation remains consistent during the time leading up to ignition of the mixture of atmospheric oxygen and unburned products of pyrolysis and combustion.

A key aspect of ventilation leading to potential for a smoke explosion is that ventilation must be sufficiently constrained for the fire to become ventilation limited and transition from flaming to smoldering combustion but must be sufficient to allow air intake to bring mixture of unburned products of pyrolysis and combustion and air into the flammable range.

Temperature

In Sutherland’s (1999) research, the compartment temperatures immediately before the occurrence of smoke explosions ranged between 319o C and 362o C. Chen (2013) reported compartment temperatures immediately before the occurrence of explosions ranging from 300o C to 500o C. Rasoulipour (2022) reported similar results with temperatures ranging from 330o C to 397o C prior to occurrence of a smoke explosion. Fleischman, Madrzykowski, and Dow (2024) reported temperatures at multiple levels and locations within the compartment. The upper level temperatures near the wall closest to the burning fuel package ranged from 394o C to 703o C. Near the opposite wall, closest to the vent opening, the upper level temperatures ranged from 377o C to 555o C. The lower level temperatures near the wall closest to the fuel package ranged from 220o C to 492o C. Near the opposite wall, closest to the vent, the temperatures ranged from 195o C to 343o C.

Interestingly, the temperature ranges in experiments resulting in a smoke explosion in the fire compartment are like the minimum temperatures required for the occurrence of a backdraft. However, backdrafts may result from autoignition or piloted ignition, where this is not the case with smoke explosions which are dependent on piloted ignition from a glowing ember or flame.

Despite temperature being identified as a factor in the occurrence of smoke explosions within the context of the research conducted, temperature may be correlated with the occurrence of smoke explosions in the experiments but may not be a requisite condition in all cases as many products of pyrolysis and combustion remain flammable at lower temperatures.

Rasoulipour (2022) examined the flammability of pyrolizates from medium density fiberboard (MDF) and plywood. These engineered wood products were placed in a pyrolysis chamber heated with a liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) burner; the pyrolysis products were captured in a gas storage container. The pyrolizates were tested for flammability at temperatures ranging from 15o C and 22o C at 4 hours and 72 hours after they were generated. For fresh (4 hours after generation) MDF pyrolizates the LFL was 21% and the UFL was 41%. For fresh plywood pyrolizates the LFL was `18% and the UFL was 41%. For both MDF and plywood, the LFL and UFL were slightly lower after 72 hours. Rasoulipour speculated that the reduction in flammability limits after aging could be due to either condensation of volatiles or chemical reactions in the gas storage chamber.

Overpressure

Smoke explosion and backdraft may both be described as overpressure events (OPE), but there is no clearly defined consensus definition of the extent of overpressure that is necessary for a rapid fire progression event to be classified on this basis.

Croft (as cited by Rasoulipour, 2022) defined the smoke explosion as a rapid propagation of a flame accompanied by a pressure wave in the order of 5 kPa (0.72 psi) to 10 kPa (1.45 psi) that could result in the breaking of windows and the expulsion of flames. Chen (2013) identified a lower pressure for smoke explosions, stating “the pressure difference caused by the explosion inside the compartment has to be at least 27 Pa [0.027 kPa] for it to be considered as a smoke explosion.

Most research examining the effects of overpressure or blast effects on structures has focused on explosions occurring outside the structure. The effects of blast overpressure on buildings may be quite different when the explosion occurs inside the structure. However, this data provides a starting point for understanding the potential impact of an overpressure event related to rapid fire progression such as a smoke explosion. An overpressure of 1 psi is sufficient to cause window glass to shatter, of 2 psi can cause moderate damage (windows and doors blown out and severe damage to roofs), and an overpressure of 3 psi may result in collapse of residential structures (mineARC, 2025)

Fuel

Based on examinations of actual commercial and residential overpressure events and experimental data, Fleischman, Madrzykowski, and Dow (2024) identified that potential for a smoke explosion increases when the fire involves a large surface area of smoldering fuel such as wood.

Research Limitations

While research to date examining smoke explosions has improved understanding of this phenomena, it has several significant limitations.

- Research has focused on smoke explosions occurring in the fire compartment and has not examined the occurrence of this phenomenon in compartments or void spaces adjacent to or remote from the fire compartment.

- The fuel used in experimental research into the smoke explosion phenomena has been limited to wood products while fuel loads in the built environment are considerably more complex and varied.

- Experiments have been limited to a single compartment and as such have not examined the impact of smoke migration and accumulation in a multi-compartment enclosure.

Given these limitations it is important for this research to inform understanding of the smoke explosion phenomenon, but to remain cautious about broadly generalizing the results when dealing with fires in the built environment.

Up Next

The next post in this series will examine indicators of potential for a smoke explosion and tactics for mitigating or reducing the potential for a smoke explosion.

References

Bakka, M., Handal, E., & Log, T. (2020). Analysis of a high-voltage room quasi-smoke gas explosion. Energies, 13(3), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13030601

Bengtsson, L. (2001). Enclosure fires. Karlstad, Sweden: Räddnings Verket.

Chen, Z. (2013). Smoke explosion in severely ventilation limited compartment fires. Retrieved June 16, 2025, from https://bit.ly/4472aUB.

Chitty, R., (1994). A survey of backdraft. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://bit.ly/3T2wKtf.

Drysdale, D. (2011). An introduction to fire dynamics, 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Fleischmann, C. & Chen, Z. (2013). Defining the difference between backdraft and smoke explosions. Procedia Engineering, 62, 324 – 330.

Fleischmann, C. (1994), Backdraft Phenomena. Final Report. Retrieved May 27, 2025, from https://bit.ly/4dG9T0s.

Fleischmann, C., Madrzykowski, D., & Dow, N. (2024). Exploring overpressure events in compartment fires. Fire Technology, 60, 1867–1889. Retrieved June 26, 2025, https://bit.ly/4kOKlB0.

Gann, R., & Bryner, N. (2008). Combustion products and their effects on life safety. In A. Cote (Ed.), Fire protection handbook (20th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 11–34). Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA). (2024) Essentials of firefighting, 8th ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications.

Karlsson, B. & Quintiere, J. (2000). Enclosure fire dynamics. New York: CRC Press.

Lambert, K. & Baaij, S. (2011). Brandverloop: technisch bekeken, tactisch toegepast. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sdu Klantenservice.

McAllister, S., Grumstrup, T. (2023). Burning rate of wood cribs with controlled airflow. Fire Technology, 59, 3473–3492. Retrieved June 26, 2025, from https://bit.ly/4evzlWQ.

mineARC. (2025). The effect of blast overpressure on buildings and the body. https://bit.ly/4kbu7AM.

Parkes, R. (1996). Under-ventilated compartment fires – a precursor to smoke explosions. Retreived June 16, 2025, from https://bit.ly/4n4O3YB.

Pitts, W. (1994). The global equivalence ratio concept and the prediction of carbon monoxide formation in enclosure fires (NIST Monograph 179). Retrieved June 25, 2025, https://bit.ly/4kry2tr.

Rasoulipour, S. (2022). Experimental investigation of the smoke explosion phenomenon. Retrieved June 11, 2025, from https://bit.ly/43XccaI.

Steward, P. (1914). Dust and smoke explosions. National Fire Protection Association Quarterly, 7, 424-428.

Sutherland, B. (1999). Smoke explosions. Retrieved June 16, 2025, from https://bit.ly/463HNtU.

Thomas. P. and Nilsson, L. (1973) Fully Developed Compartment Fires: New Correlations of Burning Rates. Retrieved June 26, 2025, from https://bit.ly/40nz0iV.

Underwriters Laboratories Fire Safety Research Institute (UL FSRI). (2025). Backdraft and smoke explosions. https://bit.ly/4lRIP19.

Wooley, W. & Ames, S. (1975). The explosive risk of stored foamed rubber. Borehamwood, UK: Building Research Establishment.

Wu, C., Santamaria, S., & Carvel, R. (2019) Critical factors determining the onset of backdraft using solid fuels’ Fire Technology. Retrieved June 26, 2025, fro https://bit.ly/44gbsO3.